- Alzheimer's disease is the most common type of dementia and is thought to be influenced by both climate and genetics.

- Research suggests that microorganisms may also contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease, but the pathways by which they enter the mind have been unclear until this point.

- Currently, a review from Australia found that one bacterium, Chlamydia pneumoniae, enters the brain via the olfactory nerve from the nose, leading to an improvement in the amyloid beta plaques that are normal for Alzheimer's disease.

- The creators suggest that nose poking damages the nasal lining, making it easier for microscopic organisms to access the olfactory nerve and enter the cerebrum

Nose picking is an inclination that is for the most part considered terrible, however harmless. In any case, research from Griffith College in Queensland, Australia suggests that the event is unlikely to be nearly as random as recently assumed.

The research, distributed in Nature Logical ReportsTrusted Source, shows the way by damaging the nasal depression in mice, microorganisms can enter the mind via the olfactory nerve.

A timely conclusion is essential

Dr. Guite: How do you see the future of dementia and Alzheimer's disease?

Paula: It's interesting. I think in our circumstances, assuming we are honest about everything, it is beyond the point of no return for any treatment for my mother. For our purposes, it's just that she's protected, that she's taken care of, that she drinks…

You know, my question is when do individuals go to their PCP for a conclusion or a brain scan? Because, you know, we didn't see it for her situation, it was past the point of no return. I'm not saying they could have stopped it.

In any case, when do you imagine we want to get to it and not really last until the end? Because whenever you have a conclusion, you know, there's not much you can do, and it's miserable, it's a game of cat and mouse, and we don't have the foggiest idea what's in store for us. We had no advance notice, it couldn't be helped in advance.

Dr. Ameen-Ali: I agree that [getting] an analysis as far in advance as conceivable might be the best thing you can do, really. In addition, it can be really difficult because often these early symptoms can simply be excused as aging or not being critical enough.

[However] the earlier the conclusion, the better, in light of the fact that [then] the best medicines will be. They cannot stop the disease, but they can basically affect the side effects of the previous ones that are transmitted.

In fact, I feel that in the future we should be able to analyze much earlier to have viable drugs. Moreover, when it comes to drug development, it is unlikely that we will have one single drug that will have a huge effect. Since there are a lot of these different potential disease systems, almost certainly, we will require different drugs that will be directed together, as well, that will significantly affect the movement of the disease.

Paula: Do you feel like we might reach a point where dementia testing or diagnosis is something like you would have for breast disease screening that becomes a normal part of your regular clinical self-care?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: I suspect. Assuming we have better mental tests that are more sensitive to particular kinds of memory decline, I suppose, on the basis that different kinds of memory decline at different rates.

In case we have sensitive tests, we can certainly control them at a certain age when your hazard increases. And then ideally it will lead to people being given the previous frequency when the disease is in its earliest stages. Plus, it's my thought process that will totally affect dementia later on.

Once in the mind, some microorganisms revive the affidavit of amyloid beta protein, which can lead to the development of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Amyloid beta structures the plaques thought to be responsible for the vast majority of the side effects of the promotion, such as cognitive decline, language problems, and moody behavior.

Currently, Promotion influences only 6 million individuals in the US, with numbers expected to reach 14 million trusted sources by 2060.

Nose to mind: immediate progress

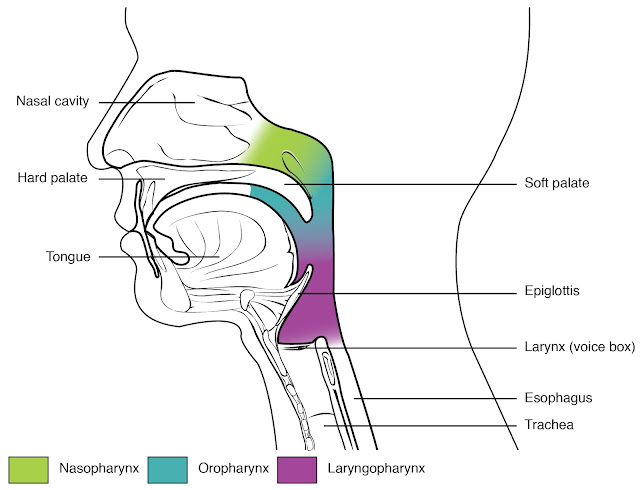

The olfactory nerve leads directly from the nasal cavity to the cerebrum. Microbes that enter the olfactory nerve can thus bypass the blood-cerebrum barrier that normally prevents them from entering the mind.

A review performed in mice showed that Chlamydia pneumoniae, a bacterium that causes respiratory infections such as pneumonia, used this course to get close enough to the focal sensory system.

Cells in the brain responded to the C. pneumoniae attack by rescuing the amyloid beta protein. Amyloid beta protein develops into the plaques that are a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease.

Prof. James St John, Head of the Clem Jones Community for Neurobiology and Foundational microorganism Exploration, Griffith College, Brisbane, was the regulating author of the review. He told Clinical News Today:

"Various investigations have shown that Chlamydia pneumoniae is available in Alzheimer's plaques in humans (using post-mortem investigations). Be that as it may, it is not known how the microorganisms get there and whether they cause the pathology of the promotion or are simply associated with it."

"Our work in mice demonstrates a way that similar microbes can quickly climb up the olfactory nerve and trigger pathologies like Promotion," he said.

Linking Microorganisms, Infections, and Brain Problems

This study confirms several studies that have suggested a link between microbes and dementia.

In 2008, a study suggested that C. pneumoniae contamination could trigger late-onset Alzheimer's disease.

"We think there are many microorganisms that could contribute to the beginning of the promotion. For example, herpes simplex infection has been implicated in several investigations. It is also possible that it requires a mixture of organisms and hereditary traits. We as a whole have microorganisms/infections in our minds, but not all of us get the promotion, so it may very well be a mix of organisms and genetics that lead to pathologies and side effects."

"Similarly, we think it might be a long slow cycle. So we don't feel that getting microbes into the brain means you're going to get dementia a week from now. All things being equal, we think the microbes set off a slow movement of pathology that can require a very long time to produce side effects," he added.

"Viral commitment to Alzheimer's disease is a fascinating area of research in this affiliation, but until now there have been no convincing circumstances and logical outcomes that people remember. Alzheimer's disease is a terrifying disease with many contributing variables." given that we really want to explore all avenues, there are various logical causes that contribute to the hidden science of disease."

—Dr. Heather Snyder, vice president of clinical and logic relations for Alzheimer's Disease, who was not associated with the review.

Research in individuals

This study showed that C. pneumoniae effortlessly made its way from the nose to the cerebrum in mice, so the researchers are now expanding their investigations to individuals.

"We have the moral support to start a concentration in people to be directed in Queensland, Australia. We will secure individuals with the starting stages of late-onset Alzheimer's disease and then find out what microorganisms are available in their nose and what the quality and protein changes are." happening," said MNT prof. St John.

"It is certainly conceivable and would be really important to verify whether the results of this fascinating concentrate in mice can be extrapolated to individuals."

—Dr. Emer MacSweeney, president and consultant neuroradiologist at Re:Cognition Wellbeing, who was not involved in the review

In addition, there are various examinations, as Dr. Snyder outlined:

"This particular review looked at mice, and mice are not humans. While this paper shows affiliation, we want this work to be replicated in humans and to better understand if there is more to it than affiliation."

"In any case, ongoing work is planned to resolve some of these questions. The Alzheimer's Affiliation is currently funding research from the Cedars-Sinai Clinical Center to further understand the possible link between Chlamydia pneumoniae and Alzheimer's disease." the cerebrum is changing,” added Dr. Snyder.

Bad effects of nose poking

Bottom line, will your chances of promotion increase? Despite the fact that research follows a clear causal relationship, the tendency to pick one's nose may also have other gambling effects on well-being, including:

- the presence of infections, microbes and various impurities in the nose,

- the spread of microscopic organisms and infections from the nose to surfaces in the palate,

- damage to the tissues and patterns inside the nose.

- Research so far shows that this damage and the presence of microbes can increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease.

Prof. St. John advised that one should stay away from nose picking and nose hair pulling. "If you damage your nasal covering, you can increase the number of microbes that can appear in your mind," he said.

All in all, should individuals fight the temptation to get those hoes back? Dr. MacSweeney takes it very well, he can be clever:

"We don't know today that individuals should be encouraged not to pick their nose, but rather [it] seems reasonable to opt for emergency care given these early results in mice."

In discussion: New circuits in dementia research

A huge number of individuals across the planet are living with a type of dementia that seriously affects both their own and their caregivers' personal well-being. The specific causes of dementia remain unclear, but scientists continue to learn more about its systems. This section of the Discussion looks at some of the real factors of dementia and presents new directions in dementia research.

Plan by Andrew Nguyen.

Dementia is a neurocognitive condition that refers to a number of side effects associated with cognitive decline and decline in mental abilities.

The most well-known type of dementia is Alzheimer's disease, which affects a large number of individuals worldwide. According to information from the Habitats for Infectious Prevention and Anticipation (CDC), up to 5.8 million individuals in the US alone had Alzheimer's disease in 2020 from a trusted source.

Alzheimer's Disease 2019 research shows that north of 850,000 individuals were living with dementia in the United Kingdom that year, and a total of more than 55 million individuals from a trusted source are living with dementia, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

There are a few drugs that can help alleviate some of the side effects of dementia, but most types of dementia are currently serious, and scientists continue to research the components that cause the condition, with the ultimate goal of developing better drugs and countermeasures.

In our latest installment of the Discussion, we spoke with Paula Field, who is a parent figure to her mother, who lives with Alzheimer's, and Dr. Kamar Ameen-Ali, who lectures in biomedicine at Teesside College in the Unified Realm and who has some experience in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's.

This article provides an altered and abridged recording of this portion of our digital broadcast. We've added a reference connection to be able to enter referenced research discoveries. If that's not too much trouble, pay attention to a digital recording — under or on top of your favorite podium — for the entire interview.

Dementia: Definition and hereditary hazard

Dr. Hilary Guite: We should start with an outline of dementia and its causes.

Dr. Kamar Ameen-Ali: In general, I feel like it's great that we're researching dementia to understand what we mean by it. You could often hear individuals use it interchangeably with things like Alzheimer's, but these are extremely specific things.

Dementia, we kind of portray it as an umbrella term. It shows a lot of side effects, it's a clinical condition - these side effects are often associated with memory impairment. In any case, to be diagnosed with dementia you must also have impairment in at least one other mental area - it could be character, it could very well be visual-spatial skills, for example.

Also, as I mentioned, dementia as a clinical condition is not interchangeable with something like Alzheimer's disease, which is a type of brain infection that causes dementia.

Dr. Guite: Is dementia hereditary?

Dr. Ameen Ali: It depends on what brain disease we mean. So, on the off chance that we're going to discuss Alzheimer's—which I think is really smart because it's the most common brain disease that causes dementia—there are a few types of Alzheimer's that are genetic and a few types that aren't.

The most common type of Alzheimer's disease is what we call inconsistent Alzheimer's disease, and this accounts for 97% of Alzheimer's cases. So 3% of Alzheimer's cases will have that known hereditary onset, and that's caused by hereditary changes.

So only a small level of actual Alzheimer's cases have this inherited, known genetic link.

A real effect

Dr. Guite: Much obliged. So Paul, you have been caring for your mum with dementia close to work. Could you ever tell us what you noticed before?

Paula Field: Indeed, I am. I think my sister and I saw before that there were some problems with her memory after my father died. I believe she had already started to develop some type of dementia before, but [our parents] helped each other. Plus, I think [our father] helped her with a lot of the everyday things.

After he left, I think it became a lot clearer [that something was wrong], in any case, you know, at that stage we weren't sure if [her side effects were] a kind of despondent thing. Still, she made steady progress. Plus, it probably took about half a year for us to kick the bucket before we realized that, you know, we probably expected to take her to a specialist and find out that this thing was going on.

Dr. Maria Cohut: Paulo, how did it affect you and your sister financially and during your daily life?

Paula: I think you could talk [to our mother] in the good old days. [My sister and I] were both working all day, visiting at the end of the week, so we were actually there all the time. As for the monetary effect, it definitely wasn't at that stage, we just kept going to nobody's surprise. At that stage we didn't have any [other] carers or anyone, we just went in as often as possible.

Then, when it came to that moment that we had to take her to the specialists for her most memorable memory test, and when the results came back, that's the point where we had to start thinking [arrange] more consideration. In addition, this is due to my sister going home from work for seven days and enjoying two evenings with her mother every week.

He's been doing it for almost 4 years now. On top of that we have other carers who come to us about twice a day and at the moment they need to get her up, give her a couple of lunches and another at night to give her some sort of dinner. They do it about 4 days each week and we have the rest.

How specialists analyze dementia

Dr. Guite: What kinds of cycles and demo cycles are going on these days?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: There are different kinds of inspection that should be possible, [like] PET outputs and X-ray inspections.

As for how well they can contribute to a conclusion about brain diseases? I think this is problematic because, assuming we are looking for brain changes that are related to, say, Alzheimer's disease, the question is how we might see this pathology in the mind at any given moment during everyday life. Something like Alzheimer's disease can be analyzed post-mortem when we can confirm that the neurotic changes in the mind are indeed there.

However, something like a PET or a CT scan or an X-ray scan, they can see if there's a general decline in the mind, and that's something that we would hope to find in something like Alzheimer's, particularly decline around the hippocampus, which is part of cerebrum, which is responsible for various memory processes.

So, in part, these mind probes can help find the specific brain disease that triggers dementia, but we have to remember that this can always be confirmed post-mortem.

Dr. Guite: You talked about the breakup, what is the significance of that?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: Decay is basically where the tissue of the mind is decaying. If you somehow managed to see a mind that disintegrated, you would essentially see a certain region of the cerebrum shrink.

Dr. Guite: My understanding is that the new PET tests can look at how the mind uses supplements, like sugar, and that they can show if there are a few proteins that misfold. Could you ever understand what these proteins are - amyloid and tau - and how important they are?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: Amyloid and tau are the typical neurotic peaks of Alzheimer's disease. Amyloid is a protein that clumps together in the brain and in structural plaques, and that's exactly what we find in Alzheimer's disease.

These plaques then impair the ability of the neuron cells and this in turn causes many of the mental problems we discussed earlier.

Plus there's tau, which is [another] protein in the brain. Once again, this is another typical neurotic element of Alzheimer's disease. It is typically a protein inside the axons of nerve cells and helps shape what we call microtubules, which are responsible for transporting accessories inside the phones.

What we find in Alzheimer's disease is that it clumps into these nodules and that disrupts the cellular ability and affects how the cells talk to each other.

Changes in character and behavior

Dr. Guite: Paulo, after this basic stage and cognitive decline, what else did you start to see [in your mother]?

Paula: We really saw that she turned out to be very limited. She didn't move out of the house, she started leaving peas on the stove. Plus I think, you know, that was where we started going, "Eek, this is getting very significant."

In fact, he has some kind of instinctual inclination so that by the end of the day he turns off the switches anyway. This is something she has done for eternity. Be that as it may, basically all other things…

She knows there is a fridge in her house and realizes there should be something on racks and places the items in the ice chest. It could very well be a packet of crisps or it could very well be a cup. He has this visual memory of the ice chest, he kind of understands what it's for, but he doesn't know exactly how to use it.

Yet there is nothing else in it. She doesn't care about herself. She definitely couldn't take medication because of the possibility that it wouldn't hydrate. She doesn't wash [herself]. In case we ask her to clean or something, she is very alert, she will go into the washroom, close the entrance, deny you access, and then come out again.

She actually accepts that she prepares dinner by herself, she actually accepts that she can do everything she always does. Basically, I don't believe it's distancing. I think she [thinks] it worked out, that's probably how she made it.

He has no idea who my sister and I are—he remembers us [as natural faces], but he hasn't the foggiest idea of our identity. She has no information about the people who come to help her every day.

She is not extremely dynamic, she basically sits on the seat normally with the TV on and explores the space.

Risk variables and what goes on in the mind

Dr. Guite: Kam, could I get back to you at any time from that stunning display of progress in changing character in behavior, what's really going on in the brain? Since you said [the changes] started in the hippocampus, which is the area associated with overseeing memories. However, there seems to be more going on. What can actually happen as dementia progresses?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: That's one of the complexities of these kinds of brain diseases that lead to dementia: how they can primarily affect individuals based heavily on the parts of the mind that are affected by the infection.

In something like Alzheimer's disease, we realize that the pathology progresses to specific areas. Also, as the disease progresses, it begins to affect more areas of the cerebrum, which is why you may initially see some memory problems.

Still, many individuals could excuse them as they progress in years to the point the disease progresses, from there the sky is the limit and more mental spaces begin to be affected. So as the disease progresses into more of the cortical areas, you may see more problems around language around character and then visuospatial problems that you might see later as the disease progresses into those cortical areas.

Dr. Guite: Could we ever think and understand the reason why these things happen? What are the risk factors associated with persistent infection and opening?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: Assuming you remember, earlier I referred to sporadic Alzheimer's disease—an Alzheimer's infection that occurs frequently. We would also commonly see it over the age of 65, so while we're discussing risk factors, it's related to this type of Alzheimer's disease.

We have what we call non-modifiable risk factors. These will be the dangerous qualities I mentioned earlier. Age and gender are also uncontrollable gambling factors. Age is really the biggest risk factor for something like Alzheimer's.

However, we also have these 12 adjustable gambling factors. These are the things we do in our lives that we could possibly change that can reduce our risk of dementia. Additionally, there are also generally things we can do to improve mental well-being, for the most part.

These modifiable risk factors include things like difficulty, high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, actual inactivity, abandonment... Brain injury is also serious.

Dr. Cohut: So part of the gambling factors, but additionally the preventive mediations that get a ton of press are training and social movement. It seems that the longer you stay in school and the more socially active and engaged you are, the lower your risk of dementia. And your mother Paula? What were her experiences with training and further public activity?

Paula: Little if any schooling. You have to remember that she was brought into the world in the mid-1930s. Her social public activity was very large. [My parents] had a gathering of companions when they were in their 50s and 60s. They went to siesta together and stuff like that. In any case, it was very irregular.

And then they could see their companions once in a while. However, I would overwhelmingly agree that they kind of stayed together. My father was sociable, he had a much more dynamic life.

Dr. Guite: How old was your mother when she left school?

Paula: Probably around 13. She wasn't there the whole time. You have to remember the [impact] of the war and the clearing and all these things.

Dr. Guite: What happens when we have these components of learning, hearing impairment, social contact—how can they protect against or reduce the rate of dementia?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: These risk factors that we've been talking about, we recognize that they are associated with increased risk in dementia. Yet what we're trying to figure out as researchers and analysts is: What's actually the system that links these risk factors to the type of infection that we're seeing that then triggers dementia at that point?

Given that we can do examinations where we can see if there's a huge relationship between these elements and dementia, but does the thing exactly cause something like brain damage to fundamentally expand someone's gambling and subsequently promote dementia?

I like to think of it as our investigation to understand these systems is like a black box, that we are trying to figure out what is going on inside that black box. So we have these risk factors on one side, which is the information, and then disease and pathology, which is the outcome, but what's going on inside?

It's practically similar to having risk factors and defenses. What's more, you know, it's all about that harmony between limiting your gambling factors and expanding your defensive variables.

What's more, it's a probability wheel, really, on the basis that there's no guarantee that if you do any of these things, you'll get dementia. Also, there is no guarantee that if you don't do any of the things you will be protected from it, but basically it all revolves around risk oversight.

Does neuroinflammation play a role?

Dr. Guite: I read that these 12 risk factors account for 40% of dementia cases. So you have the remaining 60% which is in your black box. Now could I ever go back to your black box? Because we have amyloid and tau and we have these risk factors, what else is going on?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: Neuroinflammation is a seriously critical area of investigation when it comes to controlling a potential component that could lead to brain diseases leading to dementia.

Not getting fired up is something I enjoy. There is a kind of safety cell in the brain called microglia, and in the mind they are involved in the provocative response.

Much of the testing I have done is related to brain injury. So I looked at these cells, these microglial cells, and both the intense firing response and the sustained provocation response due to brain injury and how that might be a tool that increases the hazard of dementia after brain injury.

So it all revolves around how the cells respond as a feature of the neuroinflammatory response in the mind. What's more, how long-term, with the hope that there will be a sustained response, because we know that neuroinflammatory responses are initially intended to be defensive, but with the hope that cells are thought to be enacted for the long haul, as they can with sustained enactment actually cause harm? Furthermore, could this be the thing that then drives the development of the pathology that we find in something like Alzheimer's disease?

Dr. Cohut: I was also thinking about some new research that looked at the mind-turning of the stomach, the connection between the microbes in our stomach and what's going on in our brain. The effect of gut micro-organisms on the mind has also been discussed with respect to dementia. So I'm wondering if this could have an effect on neuroinflammation at any level?

Dr. Ameen-Ali: It's conceivable, in light of the fact that while we're discussing neuroinflammation, it could be a major irritation. It may very well be an irritation that sooner or later occurs in an individual's life. It may very well be an aggravation that has occurred and subsequently affected the mind.

So there is the possibility of deterioration occurring elsewhere in the blood, in the body, which then triggered a fiery reaction in the brain. It's not guaranteed to be from a physical problem I'll look at in the brain, it tends to be an underlying irritation as well.

0 Comments